How Can You Not Be Romantic About Baseball?

Don't worry. This is not about sports.

How can you not be romantic about baseball?

I read an essay in school about why baseball is America’s pastime. The thesis was something along the lines of “baseball is a microcosm of the American dream.” Unlike other sports, in which only people who play certain positions are likely to score the game-winning point, in baseball, everyone gets an at-bat. Individualism triumphs. You can contribute to your team a little (getting to first base, fielding the occasional grounder) or a lot (batting in a triple, pitching a no-hitter), but everyone gets their moment in the spotlight, a chance to show what they’re made of. That’s America, or what we’d like America to be.

Not a bad theory.

An old boss of mine once asked on Twitter why baseball movies tend to be so much more poignant than movies about other sports. I posited that it’s because you can see the actor’s face as he looks up at the night sky. Directors love that shit.

To the extent that I like any sport (a tiny bit), I like baseball because it’s nonviolent, you can generally tell what’s going on, and the players look cute in the uniforms.

One more thought: in basketball and soccer and football, it’s the ball that scores the point, by going through the hoop, into the goal, or reaching the end zone. But in baseball, it’s the person who crosses the plate.

“Safe at home.” If that’s not romantic, I don’t know what is.

How can you not be romantic about baseball?

Rhetorical, obviously. It’s a line from Moneyball, the based-on-a-book-that’s-based-on-a-true-story movie about Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) and a math nerd (Jonah Hill; I don’t remember his character’s name and refuse to look it up; he got an Oscar nomination for this…) using statistics to put together their lineup. Instead of looking for that intangible mix of proven talent and potential greatness, Hill argues, Beane & co. should use a numbers-based approach to maximize their per-inning on-base average (or whatever the formula is). Not exactly romantic, but the movie has its moments.

One thing the script effectively showcases is how superstitious and vibe-y sports people can be. In a memorable scene, the team’s scouts discuss prospects from the minors, and one player is dismissed because his girlfriend is ugly. Ugly girlfriend = no confidence = will flop when he gets to the majors. Yes, these guys could use a dose of cold, hard facts.

The team’s new strategy is borne out with a thrilling winning streak, and at the end, we learn the ~stats method~ led the Red Sox to a World Series victory two years later (and changed the game forever!). Spike Jonze has a small role.

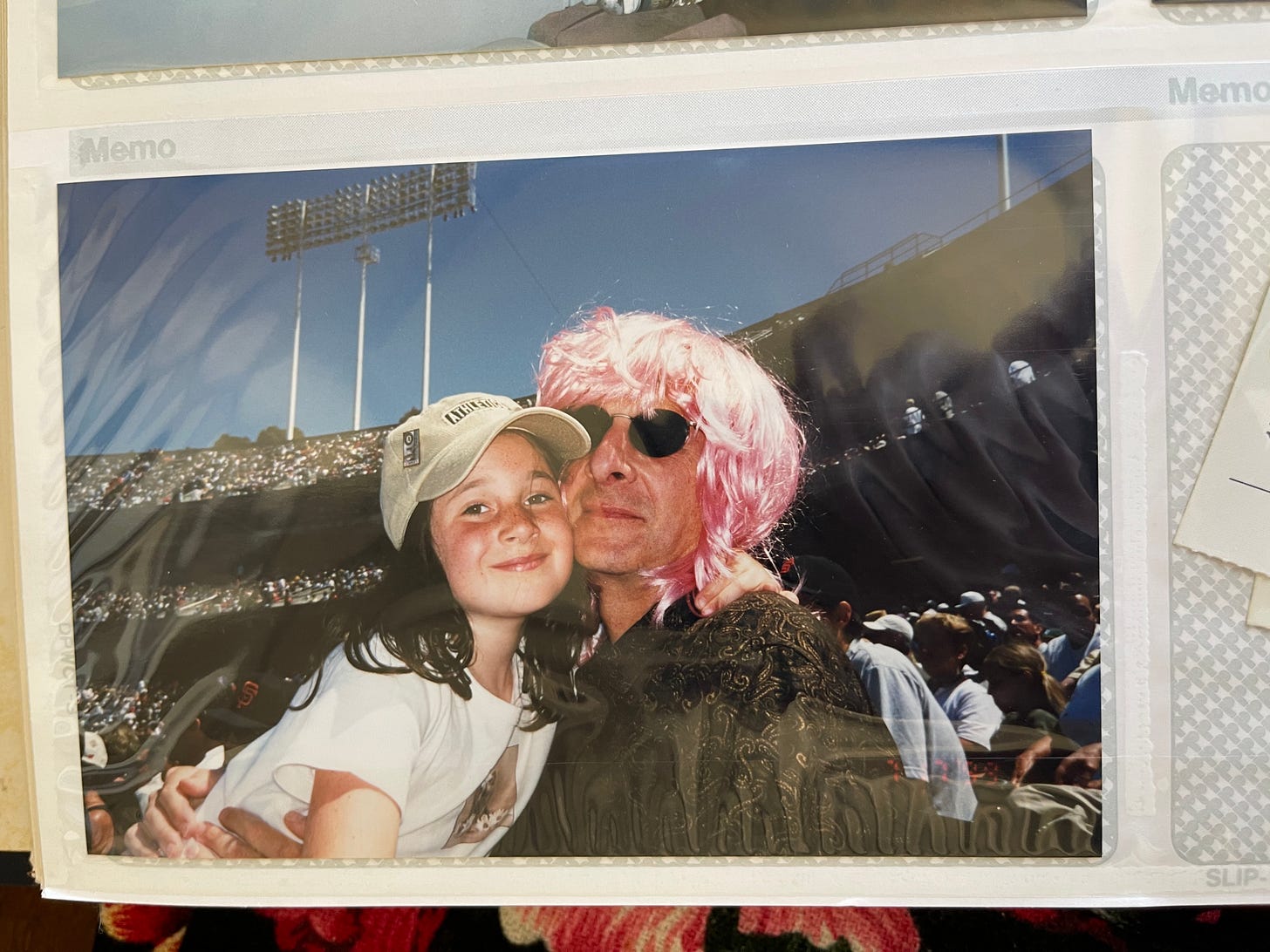

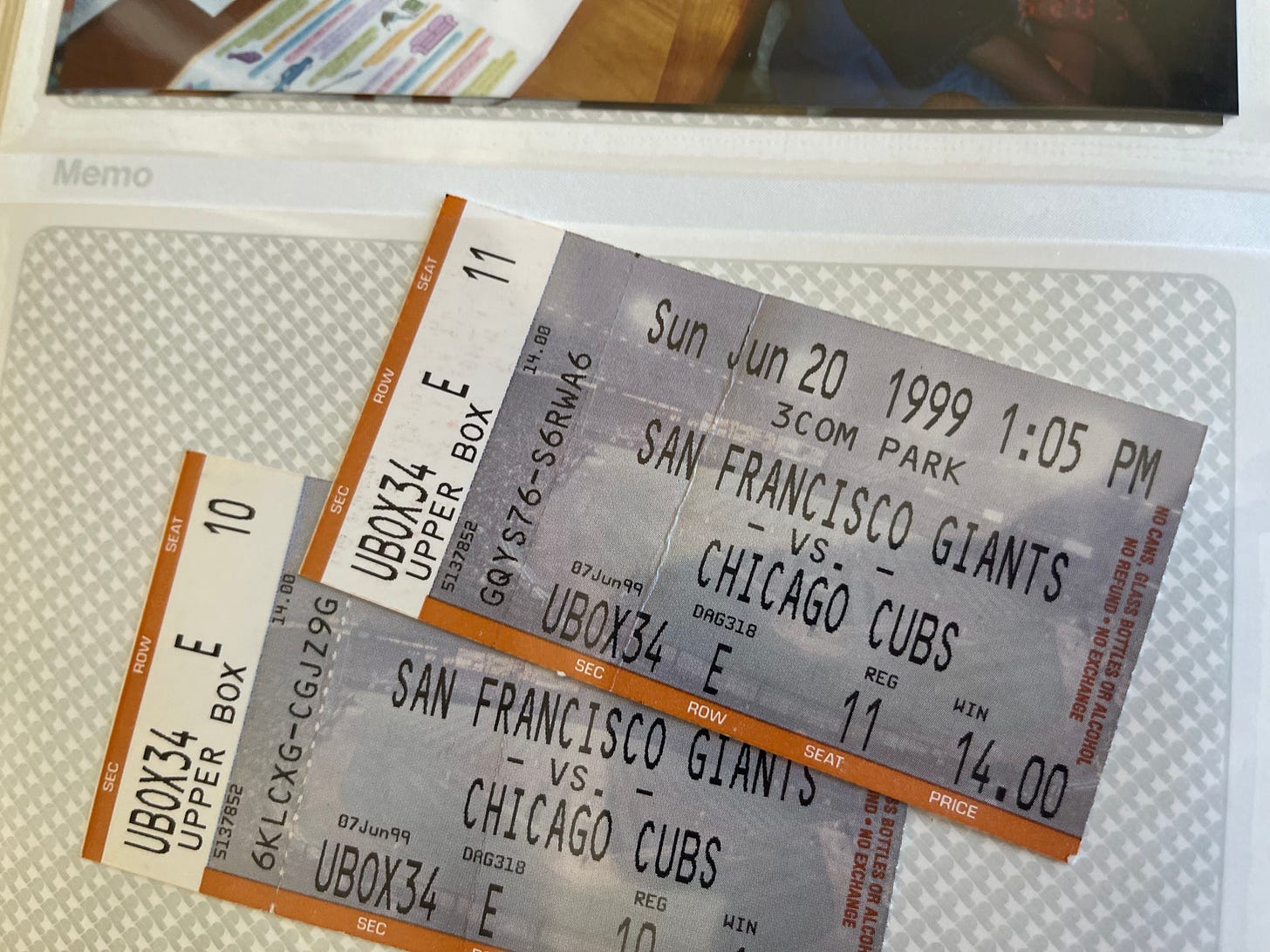

I get a little nostalgic watching Moneyball. It came out in 2011 but takes place in 2002, when I was a San Francisco kid who often crossed the bridge to catch an A’s game with her dad. I vaguely recall the announcer’s pronunciation of “Migueeeel Tejaadaaaaaa” from that era, but I wasn’t paying attention to the streak, or the method Beane used to achieve it. I was far more interested in the Nestlé ice cream sandwiches sold in the stands. Sooooo good on a hot day.

I was, however, aware of what was going on with the Giants, the other team we had tickets for. During the 2001 season, Barry Bonds hit a record-breaking 73 home runs, and I can still picture the cascade of flashbulbs going off every time he stepped up to the plate, in case this was the moment he got one step closer.

Because Bonds was such a slugger, opposing teams were understandably hesitant to let him get any piece of the ball, and he got walked a lot. We used to chant, “PITCH to BAR-ry! (clap clap clapclapclap).” It was a taunt, but also, we just wanted him to swing. Ever watch someone get walked? It’s boring.

The fact that Bonds’ feat was partly the result of steroids was an open and fairly obvious secret (necks just…don’t get that thick that fast). Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco, the Bash Brothers, had their own little home run derby at the end of the 90s thanks to the same drugs, some of which I saw from the stands (the homers, not the drug use).

It was exciting, but this era is often remembered with mixed emotions by fans. Baseball (and America) is supposed to be about hard work, God-given talent, and maybe destiny. Not to mention the long, graceful arc of the ball. Depending on how you look at it, the steroid scandals either tainted a beautiful meritocracy or revealed that this dreamy ideal had been bullshit all along.

So on the one hand we have computers putting together the most efficient rosters, and on the other, juiced-up heavy-hitters benefitting from, let’s say, artificial enhancements. Then the statistics guys realized that, actually, home runs were the best way to win games. And while you can’t actually increase the overall amount of winning in the league (every game must have a loser), all the teams put these strategies into place, and before long the league was at what you might call Maximum Baseball.

(I could draw a parallel here to our current obsession with “optimization,” a trend that’s hopefully on the way out as we start to recognize the problem of burnout.)

This was the sports version of Peak Productivity Culture, so perhaps in hindsight what happened next was inevitable, but to my understanding, the following phenomenon was a surprise…

It sucked.

It’s been twenty years since the Beane Revolution and…everyone kinda hates it! Watching players stand around waiting for the perfect pitch they can hit out of the park is dull. Watching them trot around the bases after having hit a homer is also dull. A 2011 op-ed asked, “Do Home Runs Make Boring Baseball?” As another article put it in 2020:

“The current trend - and it's statistically logical - is to so emphasize home runs even at the cost of strikeouts that games have become hours-long whiff fests punctuated by brief bursts of aeronautics.”

Games are not only less action-packed than they were in, say, the 80s, they’re also, literally, an hour longer. And while the viewership and attendance numbers don’t indicate a death spiral by any means, something’s gotta give. Some want to shorten the game. Others disagree, arguing that it’s the tension that makes the sport great (but does slow necessarily = tense?). And then there’s the issue of whether umpires should be replaced with robots.

I have answers to absolutely none of this. And to be honest, I don’t toooootally understand it, my favorite baseball moment being that one scene in Twilight (by my count this is the third time I’ve referenced Twilight in this newsletter. Not stopping any time soon!). But my take is: watching teams play the most advantageous game possible is not why people like baseball. They like drama. They like mistakes. Errors and fouls and a grown man freaking the freak out because it was in his glove, dammit, and then it just fell out. We got More, Technically Better Baseball at the expense of Funner, Excitinger Baseball, and that’s, actually, what fans want.

Amid the Statistics vs. Vibes-n-Feelings debate, Linda Holmes wrote:

“It is slap-your-head crazy to suggest that numbers and beauty are natural enemies. It's equally wrongheaded to set up the presence of unexpected events as evidence that quantitative analysis has been "transcended." Narrative richness has nothing to do with defying quantitative analysis! Sorry for the exclamation point, but it's true!”

She’s probably right, and it’s worth nothing that baseball fans and statistics fans are often one and the same, hence those little golf pencils so people can take their own notes. But for the casual viewer, maybe statistics don’t detract from the magic, but they certainly don’t add to it. An hour longer is almost always an hour duller, in my humble opinion. (You might as well read the whole article; Mike Schur, one of the most successful comedy showrunners working today, is randomly a big part of it.)

Holmes is apt to point out narrative richness, because this post is, duh, actually about AI in screenwriting (so if there are any factual errors in my history of baseball above, just, like, don’t worry about it) (and come to think of it, if there are any factual errors in the below, again, don’t worry about it).

The use of AI is one of the key issues prompting the current WGA strike. You might have heard about the strike last month when David Zaslav, head of WarnerDiscoveryHBOMaxWhatever+ and a graduate of Boston University Law, spoke at BU graduation. As he delivered an unoriginal and uninspiring oratory that sounded like a long LinkedIn post, student comrades in the stands chanted, “PAY your WRI-ters (clap clap clapclapclap).”

A bit of context: AI, as it applies to writing, isn’t actually generative but predictive (like auto-fill when you’re texting, but longer). You feed it a series of inputs, give it a prompt, and it completes the prompt by basically predicting what word is most likely to follow the previous word based on all the inputs. It will only ever write something predictable, because that is its job. Whether this is an issue of labor or plagiarism is not something I can address.

I’m also not in the guild and can’t speak to the specifics of the negotiations, but I have been picketing and reading a bit about the issue. And I think studios are poised to make the same mistake the MLB did, buying More and Bigger for the price of Exciting and Enticing. I think they’re forgetting what people like about movies.

To be clear, no one is suggesting that AI can write a better script than a person can. The points in AI’s favor are that it works faster and cheaper. It doesn’t need time off to eat or sleep, and it doesn’t need health insurance. (Also, it doesn’t have its ownd, like, artistic perspective or integrity, which execs hate anyway.)

There are a number of interesting possible uses for this technology. Combine an AI writer with an AI image generator and you could have a new Marvel movie every week! Twelve endings to a rom-com to choose from based on your own preferences! Unlimited episodes of The Simpsons! In short, we could get Maximum Entertainment. I don’t not understand how that’s attractive to studios.

My thing is…then what? After a year of weekly Marvel movies, I would imagine all but the most hardcore fans would be sick of the genre, because what people like about Marvel isn’t its quantity or the frequency of its output (though it needs to maintain both, to an extent, to keep up with demand and prevent viewers from moving on). What people like about Marvel is the human stuff! The anticipation of the next chapter, speculating on what’s going to happen, trading casting rumors and Easter egg theories. Tom Holland spoiling things so many times the studio stopped giving him real scripts. And I can’t believe I’m about to defend bad fan behavior, but they love cyberbullying the writers and directors who “mess up” their favorite characters. You can’t doxx an AI, so what’s the point?

Yes, it would be fun to scan my face and watch a computer-generated version of Titanic that stars me (in the Kathy Bates role, naturally). There may be a place for that in the future of entertainment. But I have a feeling that if someone fed a prompt into an AI that resulted in something really, really cool, they’d want to share it. Send it to their friends. Even put it on a streaming service, because people don’t want just hyper-personalized entertainment. They want shit they can talk about. That’s what it means to be a fan of something: part of a group. Maybe with matching hats and foam fingers.

You want more comparisons? I got ‘em…

I’ve heard the argument that AI is inevitable as it’s just the artistic version of the automation that already decimated the manufacturing job market. There may be some truth there. But consider that why people buy cars is very different from why people buy movie tickets. Television isn’t supposed to be cost-effective so you can get the latest model every year. It’s leisure. It’s pleasure.

The safest, cheapest and most efficient way to eat is probably to have all your teeth taken out and drink your nutrients through protein shakes. Yet people will spend time, energy and money to go to a restaurant and eat food made by human hands.

Take a crying child whose beloved dog just died. Hand her a Tamagotchi. Tell her it’ll last twice as long, require less attention, and she can even take it to school. Watch that child cry harder.

Like the teams of the MLB competing for an edge, the studios are each trying to gain an advantage in the market by squeezing their content for maximum shareholder profit. But like the teams, they’ve forgotten who this is all for: fans. And fans don’t want cheaper, faster, more. They want unpredictable, new, original.

The studios may very well automate themselves out of business. Set aside the fact that the job it would be easiest for a computer to do is actually that of an executive. Consider what would happen if the A’s replaces their whole lineup with robots that never made mistakes. Who would watch them play? After a decade of AI-scripted content, will there be any movie or TV fans left? Viewers today have a million options; the way to keep them engaged isn’t with more more more but better, cooler, weirder.

To put it in terms even a hedge fund manager might understand: if Netflix continues to make The Gray Man and Red Notice (two recent offerings that were, I am convinced, written by a chatbot)., not only will people stop liking movies, they’ll STOP SUBSCRIBING TO NETFLIX.

At their best, movies are a chance to spend 90-120 minutes taking a walk around someone else’s mind. Or maybe it’s more like opening up your own mind and letting other minds in. Seeing the way the director sees, thinking the way the writer thinks, feeling the way the actors feel. It’s risky, unpredictable, messy and totally inefficient. That’s why people love it.

Well, there I go being romantic about cínémá!

How can you not be romantic about baseball?

Picture this as a series of white-text-over-black end titles…

Bennett Miller, who directed Moneyball, has been working on a documentary about AI for five years. He also used an AI generator to create some artwork that was on view at the Gagosian a couple months ago.

Billy Beane is still with the A’s.

The numbers guy (they gave him a different name for the movie for some reason, so it’s fine that I never learned it) works for the Cleveland Browns.

Aaron Sorkin, who wrote that line, seems to be recovering well after suffering a stroke last Autumn. How very human.

Flesh and blood,

Lizzie

PS - can you believe I made it all the way through this without forcing a “strike/on strike” pun?

This is really good. Makes me think that in the dystopian possibility of AI generated entertainment, improv and live theatre will be our last hope. Maybe poetry slams. Street performers (but not those acrobatics guys who are really good at sucking money out of the crowd)